In a nutshell

- 🥚 The bread heel method uses the loaf’s end crust to trap steam, lifting the egg’s inner membrane so shells slide off cleanly—even with very fresh eggs.

- 🍞 Step-by-step: drain most water, add a splash, cover eggs with a bread heel and lid for 30–60 seconds, then peel from the blunt end where the air cell sits; replace the heel after large batches.

- 🔬 Why it works: hot steam condenses under the shell, delivering latent heat that relaxes the membrane–white bond; the heel’s porous, starchy structure holds a microclimate of humid heat.

- ⚖️ Compared with ice baths, jar-shaking, and pressure steaming, this method is fast, needs minimal gear, and keeps pitting low while preserving smooth whites.

- ⏱️ Practical wins: ideal for brunch batches and weekday prep, effective for soft, medium, or hard eggs, and delivers consistent, easy peels in seconds.

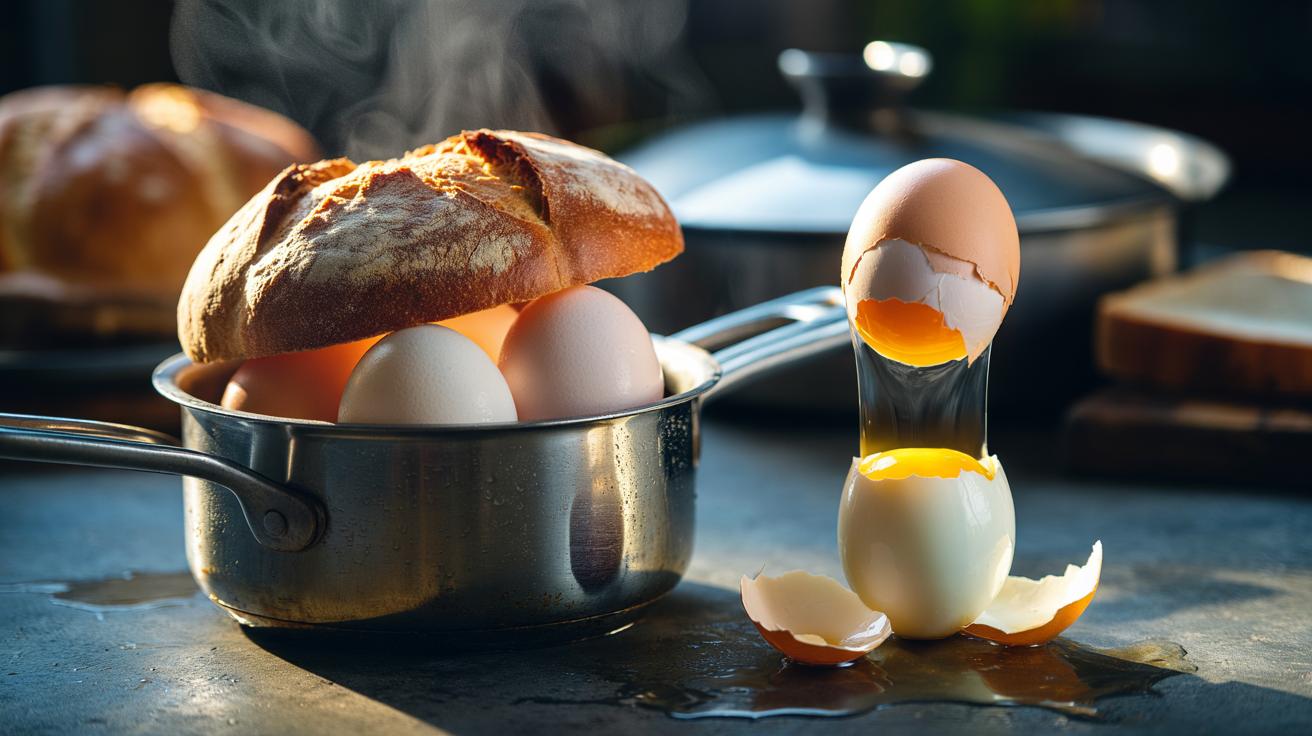

Every cook has a peeling story. Triumphs, tantrums, and the dreaded shell-studded yolk. Enter an old-fashioned hack with a modern twist: the bread heel method. It’s simple, cheap, and oddly elegant. You use the dry end crust of a loaf to turbocharge steam around just-cooked eggs, which slips beneath the shell and loosens the clingy membrane. The result? Quick peels. Neat whites. Minimal pitting. Steam gets under the shell in seconds, saving time on brunch batches and weekday snack prep alike. No gadgets. No jar-shaking theatrics. Just heat, humidity, and a bit of clever bread geometry doing the heavy lifting in your pan or bowl.

What Is the Bread Heel Method?

The bread heel method uses the end crust of a loaf as a tiny, porous steam dome. Right after boiling, you trap residual heat and a splash of water with the heel over the eggs. The crust absorbs condensate yet holds it close, creating a brief, intense steam microclimate. That vapor drives through hairline cracks and the air pocket at the egg’s blunt end, lifting the inner membrane away from the white. With the membrane detached, the shell falls off in clean sheets. This trick peels even very fresh eggs, which are notoriously stubborn because of their lower albumen pH and tighter protein network.

Why the heel? It’s stiff enough to sit like a lid yet porous enough to wick and release moisture efficiently. That balance matters. In a minute or less, the shell-membrane bond softens, so you spend seconds—not minutes—peeling. No harsh shaking that scars the white. No waiting for a full ice bath if you’re short on time. No special kit required, only a crust that might otherwise be destined for breadcrumbs.

Step-By-Step: From Pot to Perfect Peel

Cook your eggs to preference—hard-boiled around 10–12 minutes from simmer, medium at 7–9, soft at 6–7. When done, pour off nearly all the water, leaving just a thin puddle in the pan or tip the eggs into a heatproof bowl and add a tablespoon of hot water. Immediately lay a bread heel over the eggs so it lightly covers them. Clamp on the lid or cover the bowl with a plate. Swirl gently for 5–8 seconds to wet the heel’s underside and distribute heat.

Wait 30–60 seconds. You’ll see light condensation. That’s your signal. Uncover, remove one egg, and tap the blunt end to breach the air cell, then roll to crack the circumference. Start peeling from that blunt end while the egg remains warm; the loosened membrane should pull like a zipper. If resistance returns, give the pan another 20-second steam rest. For very soft eggs, peel under a trickle of water for support, working slowly to maintain the custardy center.

Tips that amplify success: don’t over-shake; you’re encouraging steam, not smashing shells. If the heel is extremely dry, flick a few extra drops of hot water onto it. For big batches, refresh the heel after 8–10 eggs—it will have given up most of its moisture-holding power by then.

Why It Works: Steam, Starch, and the Egg Membrane

Egg whites grip their shells through a delicate protein-to-membrane interface. Fresh eggs stick more because the albumen pH is lower and proteins cling tightly as they set. A fleeting burst of moist heat targets that bond. Steam penetrates via microscopic fissures and the egg’s natural air pocket, condensing between shell and membrane. As vapor condenses, it releases latent heat exactly where you need it, warming and relaxing the interface so the membrane releases. The heel’s starch and pores hold a thin film of hot moisture, maintaining an ultra-local, high-humidity zone that persists long enough to do the job.

Steam separation happens in under a minute when the eggs are fresh from the boil, because residual heat fuels the process. Cooling is still useful for comfort, but shock-cooling is optional here. Below is a quick comparison of popular methods, if you’re choosing your routine:

| Method | Time to Peel | Risk of Pitting | Works on Fresh Eggs? | Extra Gear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bread Heel Steam | Fast (seconds per egg) | Low | Yes | Bread heel, lid |

| Ice Bath Shock | Moderate | Low–Medium | Sometimes | Ice, bowl |

| Jar Shake with Water | Fast | Medium–High | Often | Jar with lid |

| Pressure Cooker Steam | Fast (batch) | Low | Yes | Pressure cooker |

In short, the heel trick borrows the precision of appliance steaming without the kit. It’s controlled humidity, on demand, powered by residual heat and a humble crust.

Handled with care, this hack slides into any routine. Keep the heel at the ready, steam briefly, start peeling at the blunt end, and let that membrane do the work for you. It saves time, preserves the egg’s smooth white, and turns a dreaded task into a near-automatic flick. Curious to test it against your current method—ice bath, jar shake, or pressure cooker—and see which wins in your kitchen on a busy morning or a big brunch weekend?

Did you like it?4.5/5 (22)